More brief notes

Hello, dear reader, and welcome to another issue of AI, Law, and Otter Things! As you read this issue, I am putting the final touches on my presentation for the workshop Methods in Legal Discipline: Post-Doctoral Insights Across Research Fields, in which I will talk about how to engage with technology in legal scholarship when you do not want to become a law and technology person. Later this week, I will present ongoing work on regulatory learning and its relationship with technology-neutral regulation and futureproofing (spoiler: it's not very synergetic). So, today's issue will be a bit more fragmentary than usual.

It features two short notes of the 'old man yells at cloud' variety: one on anticipatory governance, and the other on the proliferation of academic posters in legal events. After that, the usual recommendations (but no opportunities this time, as we near the end of the year), plus the cute otter at the end. Hope you enjoy!

Everybody has a plan until they're punched in the face

Technology regulation, in Europe and elsewhere, has an unhealthy love affair with anticipation. Faced with the possibility of being caught by Collingridge's Dilemma and regulating technologies when it is too late to effect any change, regulators all over the world try to foresee the impact of potential technologies and create laws that can cover said impact. All too often, however, these efforts lead to a considerable waste of resources and intellectual work: as Alec Muffett recently pointed out on Bluesky, the Metaverse has consumed a lot of attention in the law and technology space, but recently even Meta is trying to cut its losses on it. What is to be done?

I would argue that one way out of this problem is to place less weight on individual predictions for regulatory design. Trying to come up with ideas of what might happen is not, in itself, problematic. Quite the contrary: the exercise of trying to foresee potential risks and opportunities can lead us to re-examine certain premises we take for granted and prepare for changes. And, when we design policy responses to potential scenarios, we end up with gameplans that might be easily adaptable to situations that have similar effects, even if they are caused by different developments. (Incidentally, forecasting is not too dissimilar from science fiction in this regard, but this is a post for another day)

The problem arises, instead, when prediction is combined with other parts of the technology regulatory approaches used by the EU and elsewhere. For example, the EU's Better Regulation Toolbox establishes futureproofing as a desirable property of technology regulation: that is, regulations should be designed in a way that makes their effects resilient in light of future change. One way to do so is through regulation by design—the embedding of legal requirements into the technical requirements that guide the construction of particular technical artefacts. However, as I argued elsewhere, codifying broad requirements (such as the protection of fundamental rights) requires designers to make decisions about the connent of those requirements. This can have at least two adverse effects for policy: first, it can make the effectiveness of regulatory contingent on the decisions made by software designers (public or private); second, the particular vision embedded in software or other technologies might be hard to adjust to reflect changes in political priorities or societal values.

So, if one is making strongly binding actions grounded on a particular forecast, the least we can expect is that this forecast should be very trustworthy. Yet, that is not often the case: a correct forecast of socio-technical trends must get lots of things right, as the interaction effect between different technologies can be enough to lead things astray from the forecaster's perspective. Think of how many science fiction works could get individual technologies right (Trekkies, for instance, have long lists about what the show anticipated) and yet their overall predictions end up sounding quaint to modern observers. In short, I believe the anticipation of technological effects can be useful, but one should be wary of placing all eggs in one basket. Instead, we should use anticipation techniques as a partial guide to the future but nonetheless rely on regulatory approaches that leave margin for the unknown unknowns life might throw at us.

Against academic posters in law

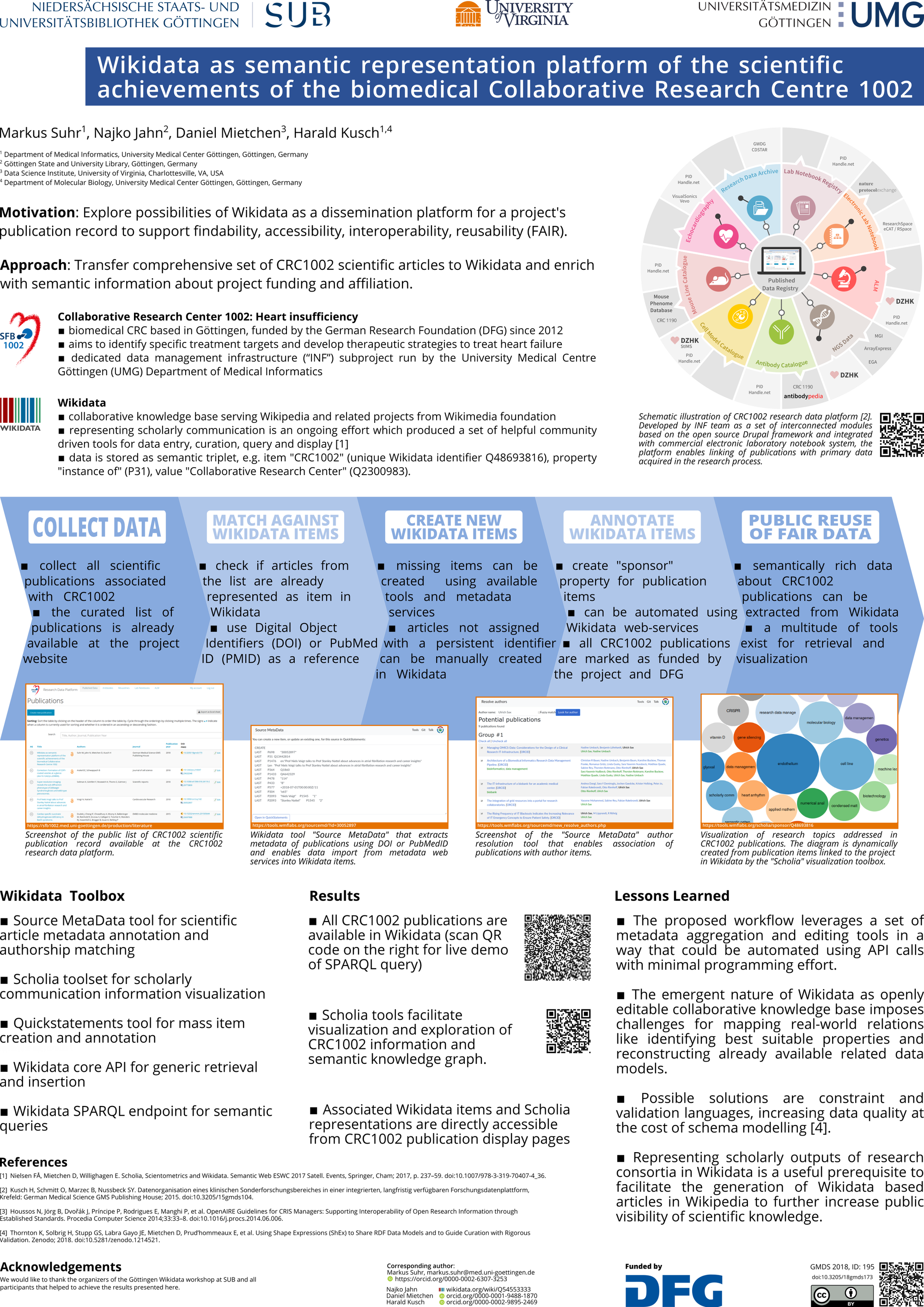

It is with a heavy heart that I must inform you that it is increasingly common to see academic conferences in law where scholars are invited to submit posters. For those of you who are blissfully unaware of the practice, an academic poster is a research output that summarizes findings in a somewhat visual form:

Posters are common in some disciplines, notably in the life sciences and informatics. As such, legal scholars already were required to create posters from time to time, for example when participating in university-wide events. However, the practice is becoming more widespread, as some law-specific conferences now invite poster submissions. While the idea of shaking up the traditionalist environment of legal academic conferences is welcome, I strongly believe posters are a net negative for scholarship, particularly when it comes to the law.

An academic poster is meant to solve a few problems of scarcity. In conferences, even the big ones, programme organizers might find themselves with more interesting talks than available timeslots. So, by fitting a poster session somewhere in the programme (or even in the coffee breaks), one could have more research exposed. Also, poster tracks are often targeted at early-career scholars, who would potentially be at a disadvantage when competing with more experienced peers for a presentation timeslot. So, by allowing those scholars to come and present their posters, one could find a way to involve them as contributors, allowing poster authors to get feedback on their research, add a line to their CV, and potentially drawing from institutional funding they could not access otherwise. At first glance, this seems a win for everybody involved.

The only problem with this idea is that posters are a terrible medium for research communication. Some years ago, Iva Cheung wrote a great post titled 'Why academic conference posters suck', in which she points the various ways in which these posters are counterproductive. I recommend that you read the entire post, both for her arguments and proposed alternatives, but there are a few points from her post that I want to highlight. From a logistical standpoint, it can be very awkward to travel with a poster for a conference. Once you are there, further problems issue from the fact that you have to actually stick by your poster, so you don't get to see much of what other poster authors are doing, in the hope that somebody will stop by your poster to have a chat. Furthermore, designing effective posters requires time and particular design skills, which are...lacking in most posters. Last but not least, the contents of posters are rarely accessible afterwards, so they end up falling into the cracks of academic conversation. In short, the medium has considerable drawbacks.

Beyond these general problems, there are some specificities of legal scholarship that make me particularly sceptical of the value of posters here. Good posters cannot help but trade off some nuance for accessibility; this is valuable in public communication affairs, but can be complicated in legal disciplines, where the crux of the findings often resides in how some tiny detail is addressed. This risk is particularly amplified when one considers how visual law projects and legal design are often geared towards the use of aesthetics as a tool for persuasion, rather than one for clarifying epistemic confusion. All things considered, I think legal scholars (especially early career ones) are better served by things like pre-event workshops, lightning talks, or ECR-specific sessions, which make it easier to accommodate text-intensive forms of legal scholarship.

Of course, none of this is to disparage the hard-working people who are trying to innovate in legal academic events. A shakeup in this domain is much needed, especially if we are to find spaces for early career scholars to flourish, as opposed to old boy networks. But I encourage you to explore other alternative forms, too. Otherwise, we might end up replicating a model that does not necessarily work even at its home disciplines.

Recommendations

- Paul N Edwards, ‘How to Read a Book, v5.0’ (University of Michigan 2015) Thanks to Thomas Streinz for the recommendation!

- Cristóbal Garibay-Petersen, Marta Lorimer and Bayar Menzat, ‘Creating Certainty Where There Is None: Artificial Intelligence as Political Concept’ (2025) 12 Big Data & Society 20539517251396079.

- Joana Mendes, ‘Law in Complex Fields: The Case of EU Regulation of Pesticides’ (Social Science Research Network, 24 July 2025).

- Nicole Manger and Mishra Vidisha, ‘Can Europe Build Digital Sovereignty While Safeguarding Its Rights Legacy?’ (Tech Policy Press, 5 December 2025).

- Patricia Owens, ‘Distinctions, Distinctions: “Public” and “Private” Force?’ (2008) 84 International Affairs 977.

- Andrew Phillips and JC Sharman, Outsourcing Empire: How Company-States Made the Modern World (Princeton University Press 2020) <https://www.degruyterbrill.com/document/doi/10.1515/9780691206202/html> accessed 3 December 2025.

- Raul Pacheco-Vega, Reading Strategies. A useful set of approaches to reading, more geared towards the social sciences but also useful for lawyers.

- Fabian Teichmann and Bruno S Sergi, ‘The EU Cyber Resilience Act: Hybrid Governance, Compliance, and Cybersecurity Regulation in the Digital Ecosystem’ (2025) 59 Computer Law & Security Review 106209.

And now, the otter

Hope you found something interesting above, and please consider subscribing if you haven’t done so already:

Thanks for your attention! Do not hesitate to hit “reply” to this email or contact me elsewhere to discuss some topic I raise in the newsletter. Likewise, let me know if there is a job opening, event, or publication that might be of interest to me or to the readers of this newsletter. Hope to see you next time!